Flying is dangerous says the mother. In Egypt, saber-rattling islamists have taken over, says the grandmother. Leaving in winter at sub zero without deicing equipment isn't just stupid but deadly, says Markus. So it's about time to look at the safety aspects of this trip.

Flying is dangerous says the mother. In Egypt, saber-rattling islamists have taken over, says the grandmother. Leaving in winter at sub zero without deicing equipment isn't just stupid but deadly, says Markus. So it's about time to look at the safety aspects of this trip.

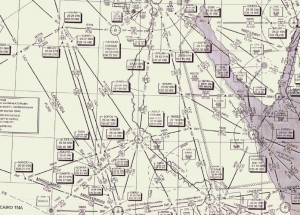

We are going to fly with a single engine aircraft according to instrument flight rules (IFR), i.e. we will go right through the clouds when they're in the way. In Europe, we are expecting winter weather and the Alps need to be crossed. The trip will include several hours over the open sea. This adds up to a few potential dangers that we have keep in mind.

Engine failure

In real life, engine failures are very rare and pretty much at the bottom of the most frequent accident causes. Most failures are due to fuel exhaustion and incorrect operation but still, it is a theoretical possibility. In case of an engine failure, a single engine piston airplane will go down but not as most people think in an uncontrolled crash but a controlled "soaring". The Cessna has a glide ratio of about 1:10 (modern gliders offer 1:40 or even better). For each foot of altitude we can advance 10 feet in distance. When flying at about 15 000 feet, we can gap a distance of about 25 nautical miles and have about 15 minutes to prepare our emergency landing. In most cases, it should be possible to find an aerodrome (no matter what kind, even a military base) or another suitable landing field. The odds are much worse when flying over low level clouds because one cannot look for a suitable landing field early on. In this case, only good maps provide some relief.

Water ditching

Directly linked to the engine failure but still worth a separate look is the emergency water landing. Even when flying at very high altitudes, we would be unable to soar to the cost if we lose the engine half way between Crete and Egypt. A water ditching would be the unevitable consequence. Several aspects play a role in water ditchings. First of all the actual ditching which one can survive or not. Our aircraft has a retractable gear which is ideal for water ditching as the biggest danger during a water landing is a loop on impact. Thanks to the retractable gear, we'd be like a very fast boat hitting the water at 50 knots. Once past the ditching one has to quickly leave the aircraft as it is most likely going to sink. It can sink within a minute but it can also stay afloat forever, this is very hard to predict.

Directly linked to the engine failure but still worth a separate look is the emergency water landing. Even when flying at very high altitudes, we would be unable to soar to the cost if we lose the engine half way between Crete and Egypt. A water ditching would be the unevitable consequence. Several aspects play a role in water ditchings. First of all the actual ditching which one can survive or not. Our aircraft has a retractable gear which is ideal for water ditching as the biggest danger during a water landing is a loop on impact. Thanks to the retractable gear, we'd be like a very fast boat hitting the water at 50 knots. Once past the ditching one has to quickly leave the aircraft as it is most likely going to sink. It can sink within a minute but it can also stay afloat forever, this is very hard to predict.

Aircraft regulations require all passengers to wear life jackets at all times while flying over the sea. Maritime stores offer comfortable life jackets at reasonable cost, using a small CO2 bottle and – most importantly – manual activation so that one doesn't block the exit should the jacket get wet before having left the aircraft. Right before the impact, it is important to open the cabin doors to make sure they don't get blocked by the water pressure (there is also the option to smash the rear window with the feet and we always carry an axe on board). The sea is colder than the human organism and therefore there is limited time until one freezes to death. In the Med in winter, this is about one hour. Getting out of the water is therefore important and this is what inflatable life rafts are designed for. For this trip, a life raft was purchased, hoping that we will never have to find out whether it actually works.

Aircraft regulations require all passengers to wear life jackets at all times while flying over the sea. Maritime stores offer comfortable life jackets at reasonable cost, using a small CO2 bottle and – most importantly – manual activation so that one doesn't block the exit should the jacket get wet before having left the aircraft. Right before the impact, it is important to open the cabin doors to make sure they don't get blocked by the water pressure (there is also the option to smash the rear window with the feet and we always carry an axe on board). The sea is colder than the human organism and therefore there is limited time until one freezes to death. In the Med in winter, this is about one hour. Getting out of the water is therefore important and this is what inflatable life rafts are designed for. For this trip, a life raft was purchased, hoping that we will never have to find out whether it actually works.

In any case, one has a lot of time to prepare the water ditching, at least 15 minutes at the planned altitude. There is a lot of ship traffic on the sea and one can choose which ship is supposed to be the savior. Better not too large so it will spot you and actually be able to maneuver. A fishing boat is probably the best choice. The landing is then planned in a fashion where the coroner will not have to note "run over by a ship" as the cause of death.

If not successfully spotted and rescued by a ship, it is important to have additional options to make others find you. There are flight plans with the goal of allowing the search and rescue services (SAR) to determine if somebody disappears and where that most likely happened but we're flying between Greece and Egypt — the former probably currently on strike and the latter occupied with street riots while we're afloat on the ocean. During descent, the radio is used to report the position and plans. Depending on the position and altitude, it is possible that radio contact cannot be established as there are no radio stations over the sea. Airliners high up are usually available to serve as message relays. In addition, the aircraft carries an ELT (emergency locator transmitter) as part of its safety equipment. The ELT can be activated manually or automatically on impact (similar to airbags in cars), sending the current GPS position and a unique identifier to a special satellite network, alarming the search and rescue service. The transmitter will continue to send its signal until either the battery is drained or the airplane sinks below the water line. In theory this could not be enough time to alarm the rescue crews so there are also PLBs (portable locator beacon). Once on the life raft, the PLB antenna is extended and activated until the Greek rescue service shows up. A PLB was purchased for this trip.

If not successfully spotted and rescued by a ship, it is important to have additional options to make others find you. There are flight plans with the goal of allowing the search and rescue services (SAR) to determine if somebody disappears and where that most likely happened but we're flying between Greece and Egypt — the former probably currently on strike and the latter occupied with street riots while we're afloat on the ocean. During descent, the radio is used to report the position and plans. Depending on the position and altitude, it is possible that radio contact cannot be established as there are no radio stations over the sea. Airliners high up are usually available to serve as message relays. In addition, the aircraft carries an ELT (emergency locator transmitter) as part of its safety equipment. The ELT can be activated manually or automatically on impact (similar to airbags in cars), sending the current GPS position and a unique identifier to a special satellite network, alarming the search and rescue service. The transmitter will continue to send its signal until either the battery is drained or the airplane sinks below the water line. In theory this could not be enough time to alarm the rescue crews so there are also PLBs (portable locator beacon). Once on the life raft, the PLB antenna is extended and activated until the Greek rescue service shows up. A PLB was purchased for this trip.

Signal flares are the icing on the cake, letting you start a firework, hoping that other ships will like the spectacle and steer to the source of it. The real flares with little parachutes are beyond our reach as we don't have the mandatory license to buy them so we have to stick to the toy variant.

Just like professional sailing crews, we have a grab bag, a water tight bag containing some emergency equipment. Before taking off for the sea leg, all things important to survival on the sea are packed into the grab bag which we would take with us on the life raft. The grab bag will contain:

-

PLB (emergency transmitter)

-

Bottled water

-

Documents (so the coast guard won't sink our raft because they think we're illegal immigrants)

-

Mobile phone (there is a chance they'd work, some large vessels have mini GSM cells)

-

Signal flares

-

Markus' collection of Victoria's Secret prospectus

Icing

Even though we're going to fly under instrument rules (IFR) and therefore are allowed to fly in bad weather and through clouds without visual references, there is a serious limitation for most small sports aircraft: icing. Clouds (or better "visible moisture") may consist of small liquid water droplets with less than 0°C. These are called "supercooled water droplets". In order to freeze, water needs a nudge, a so called condensation nucleus. Up in the skies, the air is typically rather clean and free from condensation nuclei and so the supercooled water droplets sit there and wait … until a Cessna arrives! On impact with the aircraft's structure they immediately freeze and stick to the leading edge of the wings, the windscreen, the propellor, the elevator. This causes the aircraft to lose power (propellor icing), create less lift due to the new shape of the leading edges, cause more drag while also becoming heavier. As a result, at some point the airplane will no longer be able to keep its altitude and has to go down. If it eventually gets to positive ambient temperature,t he ice quickly dissolves from the aircraft. However, in winter the freezing level often is at ground level making the thing considerably more dangerous.

Even though we're going to fly under instrument rules (IFR) and therefore are allowed to fly in bad weather and through clouds without visual references, there is a serious limitation for most small sports aircraft: icing. Clouds (or better "visible moisture") may consist of small liquid water droplets with less than 0°C. These are called "supercooled water droplets". In order to freeze, water needs a nudge, a so called condensation nucleus. Up in the skies, the air is typically rather clean and free from condensation nuclei and so the supercooled water droplets sit there and wait … until a Cessna arrives! On impact with the aircraft's structure they immediately freeze and stick to the leading edge of the wings, the windscreen, the propellor, the elevator. This causes the aircraft to lose power (propellor icing), create less lift due to the new shape of the leading edges, cause more drag while also becoming heavier. As a result, at some point the airplane will no longer be able to keep its altitude and has to go down. If it eventually gets to positive ambient temperature,t he ice quickly dissolves from the aircraft. However, in winter the freezing level often is at ground level making the thing considerably more dangerous.

Icing only occurs under certain circumstances. Ambient temperature has to be below 0°C but not colder than -25°C as then cloud mostly consist of ice crytals. The type of cloud also plays an important role in what kind of icing you get and how severe it is. Cumulus clouds generally cause more icing than stratus clouds. The worst of all are cumulus nimbus (thunderstorm clouds) — they are the feared most by pilots for other reasons, too. Luckily they are mostly found in summer.

Our Cessna does not have any deicing equipment, apart from the heated pitot tube (to determine the airspeed). We are able to enter clouds with icing but we better make sure that we get out on top of them quickly and only collect small amounts of ice. Best is having the option to decend below the cloud into positive ambient temperature. Normally, one tries to quickly climb above the weather and then only have blue sky for the whole trip. At the destination one might have to descend through clouds but this happens rather quickly (descends are faster than climbs). We will definitely have to put a strong focus on icing scenarios and this will ultimatively determine when we take off and it will be our biggest threat for this trip.

Oxygen

The higher you go, the "thinner" the air gets. From a technical point of view, air pressure decreases with altitude and so does the oxygen partial pressure. Even high up, the air still contains 20% oxygen but at such a low pressure that osmosis in the human cells no longer works. You don't get enough oxygen which is nasty because at the time you notice, it might be too late. Strange things happen to you, you get euphoric, you consciousness gets clouded (like with Markus at sea level), you get blurry vision. Larger aircraft have a pressurized cabin, simulating an altitude of 8000 feet. Starting at around 10 000 feet, one can feel the first negative effects and starting at around 12 500 feet it starts to get critical. Our Cessna does not have a pressurized cabin, so without additional equipment we'd have to stay below 12 500 feet which would negatively impact our airspeed and fuel consumption but most importantly make it a lot harder to get above the clouds, which often go up much higher. The Cessna has an integrated oxygen supply system, meaning a bottle with medical oxygen that we breathe through nose cannulas. Normal air at sea level and 100% oxygen at 40 000 feet have the same oxygen partical pressure, thus roughly the same effect on the body. We are going to fly at 20 000 ft (possibly up to 24 000 feet if required) so we're fine. An additional device helps us to use the oxygen more efficiently (you can't refill your bottle in Southern Europe or Africa). It's got a pressure sensor to determine when the person breathes and also what the ambient pressure (i.e. altitude) is and serves the right amount of oxygen at the right time.

The higher you go, the "thinner" the air gets. From a technical point of view, air pressure decreases with altitude and so does the oxygen partial pressure. Even high up, the air still contains 20% oxygen but at such a low pressure that osmosis in the human cells no longer works. You don't get enough oxygen which is nasty because at the time you notice, it might be too late. Strange things happen to you, you get euphoric, you consciousness gets clouded (like with Markus at sea level), you get blurry vision. Larger aircraft have a pressurized cabin, simulating an altitude of 8000 feet. Starting at around 10 000 feet, one can feel the first negative effects and starting at around 12 500 feet it starts to get critical. Our Cessna does not have a pressurized cabin, so without additional equipment we'd have to stay below 12 500 feet which would negatively impact our airspeed and fuel consumption but most importantly make it a lot harder to get above the clouds, which often go up much higher. The Cessna has an integrated oxygen supply system, meaning a bottle with medical oxygen that we breathe through nose cannulas. Normal air at sea level and 100% oxygen at 40 000 feet have the same oxygen partical pressure, thus roughly the same effect on the body. We are going to fly at 20 000 ft (possibly up to 24 000 feet if required) so we're fine. An additional device helps us to use the oxygen more efficiently (you can't refill your bottle in Southern Europe or Africa). It's got a pressure sensor to determine when the person breathes and also what the ambient pressure (i.e. altitude) is and serves the right amount of oxygen at the right time.

It is very important to constantly monitory blood oxygen saturation. 90% or more is a good value and passengers should regularly monitor each other. Should the oxygen system fail, there is an emergency bottle serving the pilot a few breathings and helping him with the emergency descent.

Technical problems in Africa

Just like with a car, airplanes can break down when you expect it least. Compared to cars, aircraft are ancient low tech, built in very small quantities. Avionics (for navigation etc.) come from 3rd party suppliers and are usually a mix from several decades. Only authorized mechanics are allowed to perform repairs and no two aircraft are the same. Spare parts are not available at Home Depot. Our strategy to deal with this has three elements:

Just like with a car, airplanes can break down when you expect it least. Compared to cars, aircraft are ancient low tech, built in very small quantities. Avionics (for navigation etc.) come from 3rd party suppliers and are usually a mix from several decades. Only authorized mechanics are allowed to perform repairs and no two aircraft are the same. Spare parts are not available at Home Depot. Our strategy to deal with this has three elements:

-

Common spare parts and tools are carried on board

-

In Cairo there's a US licensed aircraft mechanic (who in theory would not be allowed to work on an aircraft on the European registry)

-

If everything fails, we can fly in a mechanic from Europe

Of course it's not easy to decide which spare parts and tools to carry. You'd need two ship containers to ship the contents of Achim's hangar. This is what we determined to be worth carrying:

-

Screw drivers, monkey wrench

-

Cable ties

-

Duct tape

-

2 spark plugs

-

8 quarts engine oil

-

1 oil filter

-

air filter (in case we experience a sand storm)

-

safety wire

-

safety wire pliers

-

ground power connector (in case the battery fails)

With cable ties and duct tape, one can already solve 90% of all technical problems on this planet and in addition we'll be able to perform an oil change should this be required for any reason.

Fuel supply

From a pilot's point of view, Dubrovnik is the last stop in the civlized world. In Greece, fuel supply is already a major challenge and in Africa it is pretty much non existant. Even when being promised fuel, one should consider the consequences should this fuel not be available or look and smell different from what one expects. We are confident that the 6th of October airfield actually has AVGAS but at a bargain price of $5.20 per liter ($20 per US gallon) its attractiveness is somewhat limited. Thanks to the awesome load capacity of the Cessna and due to the fact that there is just two of us in the airplane, we've packed 4 jerry cans at 30l each (8 US gallons) so that we can carry another 120 liters (32 US gallons) in addition to the 333l (88 US gallons) found in the aircraft's wings. That's not enough for Sitia – Egypt – Sitia so that we will either have to buy some of the precious $20 fuel or do something really naughty and mix the fuel with car gas. We'd only do this in one wing tank so that for takeoff, climb and landing we can use the pure stuff and for the enroute segment the adulterated fuel. This will work just fine but it's not according to the aircraft's certification. In any case we will be dealing with jerry cans in Egypt so we are going to carry:

From a pilot's point of view, Dubrovnik is the last stop in the civlized world. In Greece, fuel supply is already a major challenge and in Africa it is pretty much non existant. Even when being promised fuel, one should consider the consequences should this fuel not be available or look and smell different from what one expects. We are confident that the 6th of October airfield actually has AVGAS but at a bargain price of $5.20 per liter ($20 per US gallon) its attractiveness is somewhat limited. Thanks to the awesome load capacity of the Cessna and due to the fact that there is just two of us in the airplane, we've packed 4 jerry cans at 30l each (8 US gallons) so that we can carry another 120 liters (32 US gallons) in addition to the 333l (88 US gallons) found in the aircraft's wings. That's not enough for Sitia – Egypt – Sitia so that we will either have to buy some of the precious $20 fuel or do something really naughty and mix the fuel with car gas. We'd only do this in one wing tank so that for takeoff, climb and landing we can use the pure stuff and for the enroute segment the adulterated fuel. This will work just fine but it's not according to the aircraft's certification. In any case we will be dealing with jerry cans in Egypt so we are going to carry:

-

4 30l jerry cans (8 US gallons) with UN certification for the transport of dangerous goods

-

funnel with integrated filter (you never know what animals live in Egyptian fuel)

-

syphon hose (to transfer fuel from the jerry cans to the aircraft)

-

blankets for the wings so the jerry cans won't scratch the paint

Pilot errors

Human errors are the most important reason for accidents in aviation. The complexity of the aircraft, the movement in 3 dimensional space and the many influencing factors such as wind, weather, airspaces, radio communication etc. demand a lot from the human pilot — often too much. The basic ingredient for a safe flight is thorough preparation, taking into account what can go wrong and how to react in such situations. There is one thing that you never have in an emergency situation: sufficient time.

Human errors are the most important reason for accidents in aviation. The complexity of the aircraft, the movement in 3 dimensional space and the many influencing factors such as wind, weather, airspaces, radio communication etc. demand a lot from the human pilot — often too much. The basic ingredient for a safe flight is thorough preparation, taking into account what can go wrong and how to react in such situations. There is one thing that you never have in an emergency situation: sufficient time.

Friends of Markus know very well that he wouldn't go anywhere without his favorite music performed by Engelbert Humperdinck. The airplane cockpit is no exception to that rule. Therefore I have undertaken the task of coming up with a technical solution to Markus' musical needs. Of course there's something in it for me, too: when you're listening to music, you can't make your copilot's ear bleed and I can focus on more pleasant conversations (with air traffic control) and just relax and enjoy the view.

Friends of Markus know very well that he wouldn't go anywhere without his favorite music performed by Engelbert Humperdinck. The airplane cockpit is no exception to that rule. Therefore I have undertaken the task of coming up with a technical solution to Markus' musical needs. Of course there's something in it for me, too: when you're listening to music, you can't make your copilot's ear bleed and I can focus on more pleasant conversations (with air traffic control) and just relax and enjoy the view.

The Thuraya satellite phone allows for making phone calls in areas without mobile phone reception (e.g. in the air), send SMS and even emails. The charges when using it our outrageous so sorry mum, we're not going to call you to discuss the neighbor's cat. The Thuraya phone also acts as a wifi hotspot which lets us access the internet from our iPads in filght. This cannot be compared to your high speed flatrate at but but gives us the opportunity to send important messages, query current weather information and even make posts to this blog. It is all pretty new so there is no experience and at this point we do not know how well Thuraya will work in the cockpit.

The Thuraya satellite phone allows for making phone calls in areas without mobile phone reception (e.g. in the air), send SMS and even emails. The charges when using it our outrageous so sorry mum, we're not going to call you to discuss the neighbor's cat. The Thuraya phone also acts as a wifi hotspot which lets us access the internet from our iPads in filght. This cannot be compared to your high speed flatrate at but but gives us the opportunity to send important messages, query current weather information and even make posts to this blog. It is all pretty new so there is no experience and at this point we do not know how well Thuraya will work in the cockpit.